GST Is Grinding Workers Down, But Government Has Fixed Books So It's Hard To Measure Just How Bad It Is

Today, as yesterday, and the day before, and the day before, there was no work going back nine days in a row.

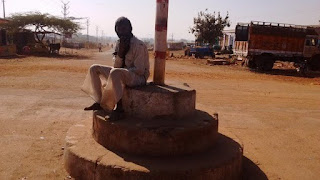

Murli Banjara, who wore a graying mustache and a fading red gamcha, squinted at the sun, which was now almost overhead. It was close to midday. While sitting for five hours, Banjara claimed to have surrendered to another day of unemployment.

"The worker pays for the GST," he added, saying that job had dried up as a result of the Goods and Services Tax levied almost a year earlier in July 2017.

For 20 years, Banjara had increased its unreliable income from plowing arid land by lifting sandstone slabs in the Bijolia quarries. He worked as a hamaal worker in the quarries, loading sandstone on mining trucks. Then, for the first time in two decades, Banjara said he was out of work.

Banjara's fellow workers said they saw drastic reductions in work opportunities even during the peak weeks of quarrying before the rains.

Every year, more than a thousand of us assemble in Shakkargarh Chowk every day, "said Heera Lal Meena, who also works as a hammock worker packing stones." This year, only 200 of us are coming here, and even 100 of us return home empty-handed every day.

The sandstone industry of Rajasthan provides an exciting example of how economic policy percolates through the many levels of the formal and informal economy of India.

Some analysts have argued that GST's short-term economic disturbances are largely temporary and that the benefits last.

However, as Banjara and Rajasthan's quarry workers illustrate, disturbances may last longer than the accumulated savings of most workers in the huge informal industry in India. In Rajasthan, for instance, sandstone production fell by 20 percent for the state as a whole and fell by half for Bijolia, one of the state's largest sandstone regions. When GST hits its one-year anniversary, its influence continues to destroy the farthest parts of the Indian economy.

The implementation of the policy has coincided with a discontinuity in the way in which the Indian economy calculates jobs, which has made it difficult to assess the impact of India's major policy changes — GST and Demonetisation — on its country's most pressing concerns: jobs.

"A major problem when evaluating the job and wage effects is that since demonetization in November 2016, there has been no national survey," said Amit Basole, Professor of Economics at Azim Premji University.

This has left economists clinging to stubbornness to describe the true health of the Indian economy.

Demonetisation and GST compelled certain companies which were able to become formal by the use of bank accounts for payments, and this can result in an increase in formal employment for example in the salary data of the Employee Provident Fund Organization, "said Jayan Jose Thomas who lectures in economics at the IIT-Delhi University.

Stoned immaculate

Rajasthan's sandstone business offers an interesting example of how economic policy percolates through India's many formal and informal economies.

Groups of eight workers in Bhilwara carry 60 to 70 kilo slabs each day on their shoulders to load one truck per day. The men bear scars from the relentless moving on their shoulders. They receive Rs 4,000 for these retrospective schemes, which they split into Rs 500-400 each at the end of the working day, double the pay for the crop.

But the double hits of demonetization and GST have rocked the stone industry.

"First of all, Notebandi wiped out all the jobs for us for 3-4 months, then the building material costs after GST rose," said Mohan Gujjar, who was with Banjara in the village of Mohbatpura to look for a job. "Small traders are struggling. Almost 75% of the" stocks "of sandstones are now shut down [ clearings where sandstone was handled by hammers and chisels ]."

The closure of the stocks affected the small dealers in sandstones who had devastated workers like him.

"When the small businessman does not have a job, who is going to hire regular wagers?" asked Gujjar.

Ranjit Banjara, a local supplier of stone, explained. "Somebody could originate from quarries earlier, open a 'stock' of sandstone and employ from 10 to 15 kaarigar (handicraft miners) and 10-12 hamaal(freight workers)," the young man explained. "But local consumers and stocks traders who only traded in cash were still battling in the month following Notebandy."

Production halved

Rajasthan makes 10% of the world's sandstone production. It is the biggest sandstone-producing state by value domestically, followed by Madhya Pradesh. Rajasthan accounts for 80% of sandstone production in India. Bijolia, along with Jodhpur and Bundi, is one of the largest production and export centres.

Arvind Rao, who has several quarries of sandstone and heads the Uparmal Pathan Khan Vyavsayi Sangh, trader's corp, said that GST has not reduced exporters ' margins, but has had a disproportionate impact on the smaller producers in Bijolia.

"Formerly," waste "or stone was conveniently used, now it has been levied by the government and GST," he says. "That has made it too expensive for smaller stone units to be processed and sold in farms or under government toilets and housing schemes."

In 2016-2017, sandstone production in the state slowed dramatically. The data from Rajasthan Mining and Geology show that production increased from 19.6 lakh tons in 2014-2015 to 21 lakh tons in 2015-2016, and subsequently fell sharply by nearly 50% to 11.5 lakh tons in 2016-2017, the latest year for which data are available.

Workers say that the drop in production has caused jobs to fall, but economists can not collect the data to criticize this claim.

The National Sample Survey (NSS) Bureau under the Ministry of Statistics and Programming conducts a nationally representative job survey every five years. The next round was set for 2016-2017, five years after the latest survey in 2011-2012.

"This survey was not carried out for some reason, however, the latest employment survey available from the Labor Bureau has been from 2015-2016 and since then, even these surveys were stopped," said Basole, Azim Premji University economist.

The five-year NSS survey has now been replaced by an annual Labor Force Period Survey. The findings of an April 2017 survey round have not yet been released. "In the absence of domestic data, experts attempt to estimate recent policies by conducting field studies," added Basole.

Deepening distress

While in Bhilwara, elderly people and workers in Adivasi still agree that life on small, arid farms and subsistence wages is difficult, they have seen things get worse last year. Almost a fifth of the 30 workers to whom this writer spoke-more than 16 percent-said he didn't even have dal once last week. Murli Banjara, who was quietly listening to Shakkargarh labor chowk talk of a clamor for work, showed the green cheque handkerchief he held up with the meal that he packed that morning – a simple lunch, dry rotating, and nothing else.

The elderly hamaal worker Ram Lal Gujjar who wore a blue turban that added height to his high, gaunt frame said that if small traders had struggled for daily wage workers for the past few months, it was difficult for disturbances and dwindling jobs to even allow themselves to eat dal or vegetables in their meals.

Thank You.

Do this hack to drop 2lb of fat in 8 hours

ReplyDeleteAt least 160000 women and men are hacking their diet with a easy and SECRET "liquids hack" to lose 1-2lbs each and every night in their sleep.

It's proven and it works every time.

This is how to do it yourself:

1) Hold a drinking glass and fill it with water half full

2) Then follow this proven HACK

you'll be 1-2lbs skinnier the very next day!